*Texas Pacific Land Trust has surged almost 2,200% since 2010

*Texas Pacific Land Trust has surged almost 2,200% since 2010

*Mineral rights offer revenues linked to Permian oil production

The hottest oil stock from the U.S. shale boom has never pumped a single barrel of crude.

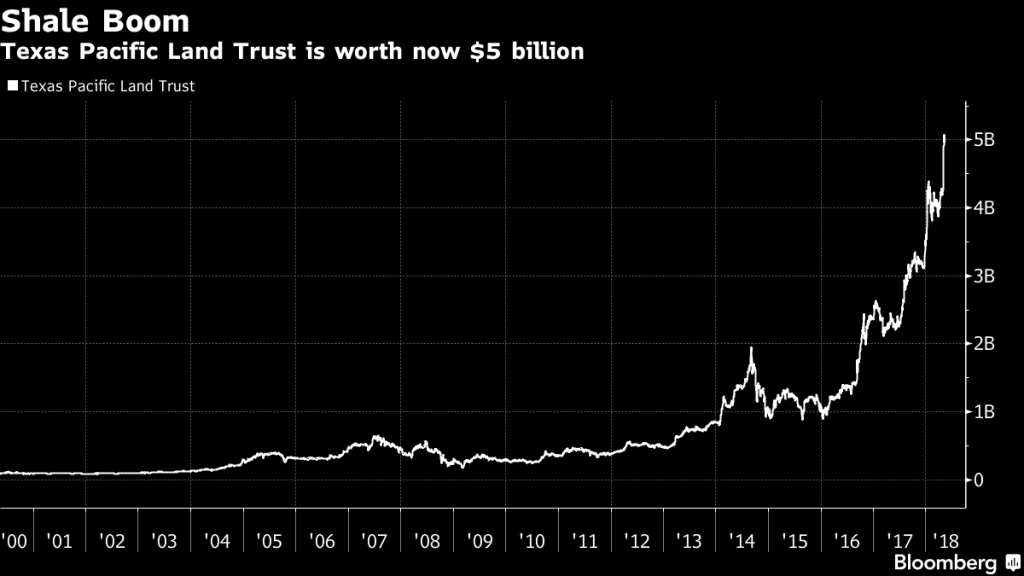

Texas Pacific Land Trust, a listed land bank created out of a railroad bankruptcy more than a century ago, has climbed more than 2,200 percent since 2010, outperforming the stocks of shale oil producers, service companies and prospectors alike. It’s now worth more than $5 billion.

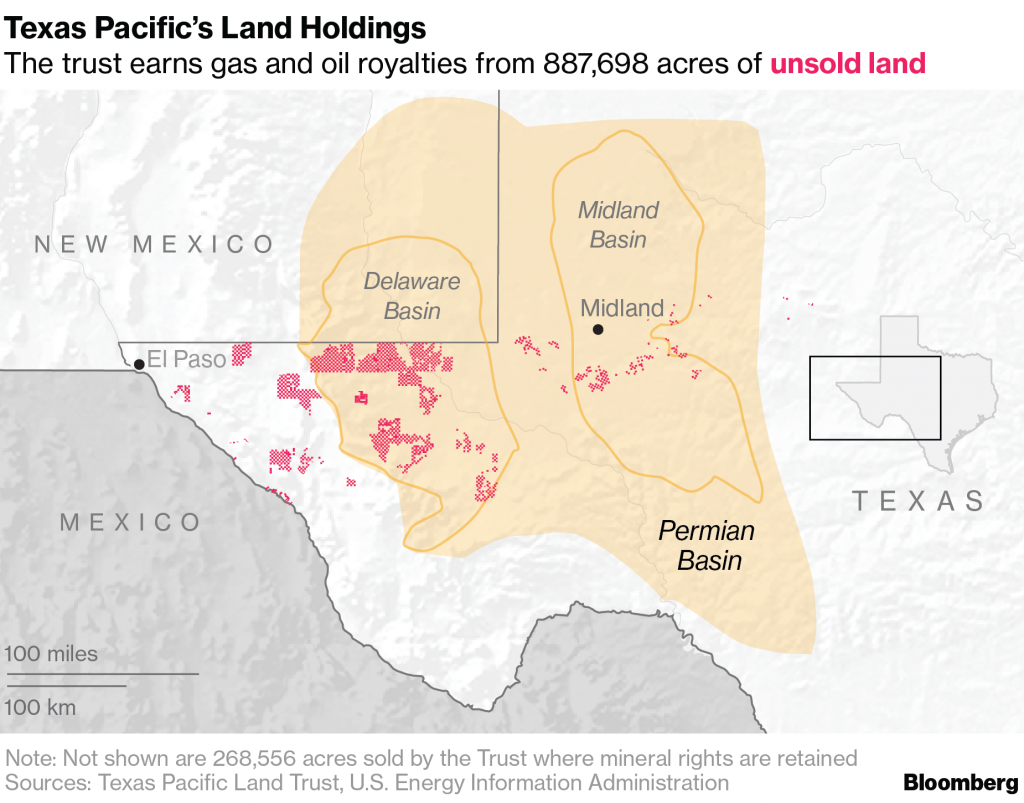

Its secret: vast tracts of mineral rights in the Permian Basin, the world’s hottest major oil region, earning revenues from the likes of Chevron Corp., which have to pay the trust when they produce from its land.

“This stock has been flying way underneath the radar for years,” said Eric Marshall, a Dallas-based fund manager at Hodges Capital Management Inc., an early investor and a top-five shareholder, according to data compiled by Bloomberg. “The real activity in the Permian is now in the areas where they have the most acreage.”

Not everyone missed the rally.

Not everyone missed the rally.

In 1995, a low-profile fund named Horizon Kinetics LLC published research on the trust titled: “How to Buy 1 Million Acres of Fine Texas Grazing Land for $20.” The fund, whose CEO Murray Stahl declined to comment, has been in and out of the stock since the 1970s. It bought it in a big way in 2008, before the rally, and now holds 1.8 million shares worth about $1.2 billion, about 20 times its original stake, according to data compiled by Bloomberg.

Born in Failure

Like many American success stories, Texas Pacific began with a failure. In the 19th century era of Westward Expansion, Texas and Pacific Railway Co. was attempting to build a railroad from Marshall in its home state to San Diego. It was granted land under federal charter to build the line but after delays and financial difficulties, the company went bankrupt in the 1880s.

The railway bankruptcy predates the Texas petroleum boom that started in 1901 with the discovery of Spindletop, the field that’s credited with leading the U.S. into the oil age.

Some 3.5 million acres, an area the size of Connecticut, were given to bondholders, placed in a trust to be sold off over time, with the proceeds going to repay creditors. The vehicle was listed in New York in 1927 with the mandate to buy back shares and pay dividends whenever land is sold, with the ultimate goal of liquidating itself.

For the first 100 years, though, much of the sun-baked land in west Texas was more desirable to prairie dogs and sand dune lizards than cash buyers. And after more than a century, the trust still retains almost 900,000 acres — and crucially, mineral rights.

The shale revolution of the mid-2000s turned this unloved land, in some of the most sparsely populated counties in the U.S., into a prime real estate.

The trust’s largest holdings are in Culberson, Reeves, Hudspeth and Loving counties, which straddle the Permian’s prolific Delaware Basin. The area is currently being drilled by everyone from Exxon Mobil Corp. and EOG Resources Inc. to Carrizo Oil and Gas Inc. and private-equity firms.

The mineral rights mean that for every barrel of oil pumped from its land, the trust gets paid. More production and/or higher oil prices equals more money.

Last year “marked the most successful year for the Trust in its 130-year history,” according to its annual report. Gross income more than doubled to $132.4 million compared with the year before. The first quarter of 2018 was also a knockout, with revenue and profit doubling again.

The stock, meanwhile, has been surging. The share price barely moved above $20 until 2000, but then rose steadily, reaching $233 before the oil-price cash of 2014. In the past two years, as production from the Permian climbed 50 percent, the stock has taken off, reaching a record-high of $677.15 on May 7.

Warning Signs

Still, there are warning signs: At current prices, TPL is trading at a price to earnings ratio of 46.41, higher than Apple Inc., Facebook Inc. and Google’s parent, Alphabet Inc., and resembling valuations seen during the dot-com bubble.

Chief Executive Officer Tyler Glover, who’s listed in the annual report as being 33 years old, and Chief Financial Officer Robert Packer, listed as 48, didn’t answer phone messages or emails requesting comment. No Wall Street analysts cover the company and it doesn’t host earnings conference calls.

Glover’s pay rose almost three times to $724,000 last year, while Packer got a similar increase to $753,000, according to the annual report.

Maurice Meyer III, the 82-year-old chairman of the trustees, was paid $4,000 last year. However, as a trustee since 1991, he owns shares in Texas Pacific worth about $44 million at current prices, according to data compiled by Bloomberg.

Viper Joins In

While it may have a unique history, Texas Pacific isn’t the only company making money from the Permian’s mineral leases. Diamondback Energy Inc. spun off its mineral rights into Viper Energy Partners LP in 2014. So far this year, Viper has climbed 28 percent.

Parsley Energy Inc.’s CEO last week said he’s “definitely looking into” doing something similar.

Most of the trust’s earnings come from oil and gas royalties. But as drilling and pipeline activity in the Permian pick up, revenues from its above-ground rights are increasing, especially water. Shale drillers use vast amounts of water, mixed with sand, to fracture the Permian’s layers of oil-soaked rock, and they also need to dispose of it once oil is produced.

Water Business

To capitalize on its large landholdings, which come with water rights, Texas Pacific started a water business last year, hiring a team from EOG Resources Inc., the U.S.’s biggest shale-focused producer. “The water services business has the potential to be even larger than its existing oil royalty and land segments,” Horizon Kinetics said in a January report.

While Texas Pacific has surged of late, Marshall of Hodges Capital says it may have further to go, over time because of its unique mandate to buy back shares.

“If they’re slowly liquidating this trust and buying back their stock, your amount of land per share increases every year,” he said. “It’s the ultimate inflation hedge and at the same time you own oil and gas royalties in what is the Saudi Arabia of North America.”

*Kevin Crowley, with assistance from David Wethe – Bloomberg