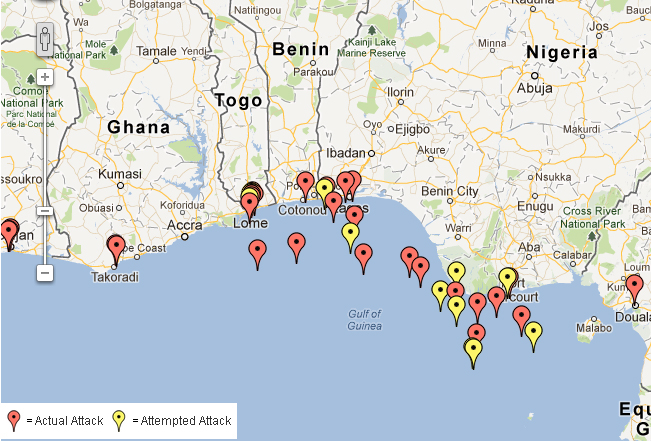

Lagos — The Gulf of Guinea has been the global epicentre of maritime crime and piracy for some time now. However, throughout 2021 the well-established trend of increasing incidents, often involving the violent armed boarding of vessels and the kidnap and ransom of crews, has declined significantly.

Such a precipitous decline in incidents is welcomed, however, increasingly this is being met with claims that the risk to commercial operations throughout the Gulf of Guinea has also lessened.

The importance of risk-based decision making for all commercial operators within the Gulf of Guinea means that it is vital that sudden and steep changes in trends of incident data are examined in detail. Indeed, by using a simple logic-based investigation of available maritime security data, it is apparent that the basis for such a decline is likely to be fragile and conditional upon loosely corelated actions, strongly indicating the fragility of any assessment that correlates a reduction in threat with a decline in incidents.

The Current State of Piracy & Maritime Crime within West Africa & Gulf of Guinea

Click here to download graphs outlining piratical activity in West Africa and the Gulf of Guinea.

Within 2021, overall incidents of piracy and maritime crime throughout West Africa have declined by 54% compared to 2020. Incidents of actual and attempted attacks and vessels being fired upon have all declined by more than 75%. Overall numbers of vessels boarded throughout the region has fallen by 32%. Incidents of vessels being boarded, and crews kidnapped have declined by 66%.

Trends and Causes

Longitudinal analysis of maritime crime data allows for observations over time and as such offers a useful but inherently limited degree of perspective through which to understand a current situation. Trend analysis alone offers little context about what factors might be driving the decline in incidents in the Gulf of Guinea and would only present commercial operators with a limited perspective against which to benchmark key risk-based decisions.

In assessing trend data alone across the past 11 months, it would be easy, but false, to conclude that a reduction in numbers is indicative of a decline in the threat from piracy and maritime crime in West Africa. Risk as a metric of measurement, often measured through the binary equation of probability and impact combined, may be said to have reduced in its proliferation and intensity, however this does not give any indication of the likely integrity of the declining trend, nor its future direction over the longer term.

With threat as the ultimate determinant factor in long term risk trends, it is here that a qualitative look at events throughout West Africa in 2021 should begin. Doctrinal definitions of threat analysis rest upon the core components of capability, opportunity, and intent. It is only through the disruption of one or all of these components that any sustained reduction in threat is likely to be achieved.

What Lies Behind the Dip in Incidents in the Gulf of Guinea?

The most significant development in 2021 in countering maritime crime and piracy in the Gulf of Guinea was the launch of Nigeria’s highly anticipated Nigerian ‘Integrated National Security and Waterways Protection Infrastructure program’, also known as the ‘Deep Blue Project’ (DBP). The first narrative worth exploring is that which equates the launch and subsequent effectiveness of the DBP with sole responsibility for the decline. The central thrust of this narrative is that the DBP has significantly degraded the capability of pirate action groups whilst providing a significant degree of effective deterrence.

The second such narrative is that piratical intent within the Gulf of Guinea has fundamentally altered, leading to a decline in piracy. When exploring the role of intent as a driver of piracy, it is vital to focus upon other associated drivers of piracy and maritime crime, as well as negative impacts upon intent, such as effective deterrence.

The third examines piratical opportunity. This focusses upon opportunity as a concept that manifests in a number of ways. Opportunity is examined principally as a concept that drives criminality as well as the physical notion of opportunity which occurs in areas where there is a high volume of viable targets and a high degree of freedom of movement.

Has Piratical Capability Reduced?

The DBP is the first integrated maritime security strategy in West Africa aimed at countering piracy. Launched on June 10, 2021, it will see the phased deployment of 16 armoured vehicles for coastal patrol, two special mission vessels, 17 fast interceptor boats, 2 special mission aircraft for surveillance of the country’s EEZ, 3 special mission helicopters for search and rescue operations, and 4 unmanned aerial vehicles.

Providing a central framework for command-and-control, Nigeria established a regional command centre based in Lagos, which ties in with regional hubs to enhance the coordination and sharing of information. Whilst the launch of the DBP and the decline in piracy in 2021 are roughly corelated in time, there appears to be little tangible evidence of causation. The data, both in terms of overall volume of incidents and the specific types of incidents, does not indicate a scenario that would fully explain such a decline. If one were to assume that the DBP’s assets were deployed into an environment of frenetic piratical activity, it would be logical to expect a high number of piratical incidents to continue, albeit marked by an increasing number of successful counter piracy operations, involving vessel interdiction and/or arrests. An example of this behaviour was seen when the Russian navy destroyer the Vice-Admiral Kulakov responded to and disrupted the boarding of the MSC LUCIA in October 2021.

A further significant development within Nigeria is the launching of the ‘Suppression of Piracy and other Maritime Offenses (SPOMO) Act’ passed by its National Assembly in 2019, providing a dedicated legislative framework through which to support the prosecution of maritime crime and piracy.

Nigeria has to date shown a willingness to publicly signpost the successful implementation of the SPOMO Act. Mr Ubong Essien, Special Assistant on Communication and Strategy to the Director-General of NIMASA, stated that the recent conviction of the 10 persons for the hijacking of the merchant vessel, FV Hailufeng II, on May 15, 2020, brought the number of pirates that have been convicted under the SPOMO Act to 20. With an approximate 16-month timeframe for conviction, the success of such operations within 2021 may not be known until a much later date.

The DBP and corresponding legislative reform have placed Nigeria in a definitive position of leadership in the fight against piracy and maritime crime within the Gulf of Guinea. However, despite the commendable efforts of Nigeria, the absence of data indicating a tangible and sustained engagement of assets in the interruption of offshore acts of piracy suggests that the launch of the DBP and the implementation of the SPOMO Act is far from solely responsible for the dramatic decline in piracy throughout the region. It is difficult to establish the degree to which assets of the DBP have engaged in offshore counter piracy interdictions and arrests. Indeed, incidents volumes had radically departed from the established trend in the months prior to the launch of the DBP. Whilst not all instances where Nigerian forces have successfully prevented attacks will make the public domain, given the significant international and commercial interest in the success of such operations, it would be irregular for such incidents to remain almost entirely absent from the public awareness. Indeed, it may be the case that these assets have successfully interdicted vessels upstream before attacks can occur, as seen in the recent case of the Danish Frigate Esbern Snare. However, were this the case, then a significant spike in the volume of arrests and prosecutions under the newly implemented SPOMO act would also be expected.

Have pirates changed their minds?

In seeking to explain the steep decline in piracy throughout the Gulf of Guinea it is important to consider the role of intent. Piratical intent is the result of a confluence of factors at several levels. At the local level, piracy is primarily driven by poverty. Additional factors include unemployment, weak governance, corruption, community violence and militancy, established subgroup hostility to the state and the presence of established organised crime. All of which drive disenfranchised young men from riverine and coastal communities towards serious organised crime and piracy.

Such is the potency of poverty; individuals are rarely deterred from engaging in crime solely because of increased resources aimed at combatting such crimes. As was seen in the case of East African piracy originating from Somali coastal communities, the presence of large multinational naval coalitions dramatically put pressure on the physical act of piracy, but groups of disenfranchised young men were only incentivised away from piracy following the launch of onshore programs of economic development and reform.

Throughout 2021 there has been little substantive improvement in these core conditions throughout the disparate communities of Niger Delta states. A situation further compounded by the impact of the COVID pandemic on national resources and international assistance. 2021 has seen an increase in riverine criminality involving attacks on local populations and riverine communities and a new militant grouping under the aegis of the Bayan-Men has unleashed a campaign of violence and disorder against multinational oil companies within the region, motivated by a perceived lack of community incentive and involvement.

Without a tangible improvement in the conditions onshore that create a fertile setting for piracy, it is near impossible to argue that there has been any alteration or deterrence against individuals’ intent to engage in piracy.

Opportunistic crime no more?

The opportunity afforded to would-be pirates within Nigerian waters and the wider Gulf of Guinea stems from two specific areas. The first is the tangible volume of available targets set against the vastness of the maritime area in which security assets are deployed. The volume of available targets in the Gulf of Guinea remains significant, with large numbers of vessels continuing to operate throughout the region. The volume of security assets deployed within this area has been vastly enhanced in recent months as a result of increased international naval cooperation throughout the wider Gulf of Guinea and the presence of additional security assets of the Nigerian DBP. Despite this, the prevailing trend of piracy until 2021 had indicated a considerable increase in the offshore capability of pirate action groups to adapt to the enhanced security presence, by conducting their operations further offshore and in areas where there is little maritime security infrastructure. Whilst the enhanced security presence throughout the region is to be welcomed and encouraged, there is little evidence that such forces are consistently denying pirates the freedom of movement and subsequent opportunity to conduct attacks.

The second manner in which piratical opportunity manifests is via the less tangible area of ineffectual governance and corruption. It is here that the greatest impact upon 2021 piracy statistics is likely to be found. The term piracy is an oversimplification for what is essentially a form of serious organised crime. One of the hallmarks of serious organised crime is its ability to occupy the ‘grey space’ between legitimate and legal enterprise and criminal network, with members often occupying official positions in business or local government. Within the southern Delta states, this ‘grey space’ of legitimacy is deeply ingrained. Ingrained corruption and ineffectual governance have given rise to a vast network of criminality that spans narcotics and pharmaceutical product smuggling, illegal fuel bunkering, militancy, and piracy.

In 2021, the UNODC, in partnership with the government of Denmark, released, ‘Pirates of the Niger Delta: Between Brown and Blue Waters’. This comprehensive report accurately describes the functional levels of a pirate action group. It specifically highlights the importance of ‘high level illegal actors and ex-militants’ as sponsors of piracy. The paper pointedly notes that “…Deep Offshore pirate groups often have a:

…sponsor, or investor, who generates – partly or totally – the initial finances needed to initiate a maritime piracy operation…sponsors likely have legitimate employment or own a business entity trading in the formal economy…

The paper goes on to state:

…local politicians are said to occasionally hire armed groups, most likely including pirate group members, to provide armed protection, apply pressure to political opponents or voters. A self-identifying pirate group member, asked to describe how his group relates to politicians answered, “For the politicians they hire us for business…”

Until 2021 Nigeria was often accused of suffering from ‘sea blindness’, a reason often cited for the disparity in security force spending and deployment of forces between northern and southern Nigeria. However, with the launch of the $195m Deep Blue Project, inaugurated by President Buhari himself, Nigeria appeared to have resolved this issue. Along with this significant financial investment came a substantial level of political focus, both domestic and international. Such a focus is highly likely to have had a detrimental impact on the freedom of movement and operations of those who occupy the described grey space of legitimacy in the southern Delta states. With Nigeria calling for an end to war risk premiums for vessels operating in its waters, there is a great deal of political investment in the success of the DBP, and it is highly likely that this investment has translated into a hostile operating environment for any would-be ‘sponsor’ of offshore piracy. This downward pressure is well displayed in the UNODC report on Nigerian piracy when the report states:

…accounts reported ex-militant leaders demanding – on direction from political leaders – that pirates accelerate a hostage negotiation, when it was seen to generate “issues that disturbed their high-value business.”

It could be argued that the intensity of the political focus, which has created an increasingly hostile environment for would-be piracy sponsors, has reduced piracy, via the ‘back door’ and regardless of cause, the effect is to be welcomed. However, such assumptions would be false. Criminality of this nature has a fluidity that is likely to adapt and overcome political pressure and will most likely lead to a return to high volumes of piracy as political focus wanes.

Summary

Overall incidents of offshore piracy may have reduced throughout 2021, yet the core components that drive piracy, and threaten vessels and crews operating within the region remain unaltered. The integrity of the declining trend can be seen to be conditional upon long term political investment and focus upon the maritime domain, which in a country of vast complexity and competing priorities and set against the backdrop of a global pandemic and uncertain an economic climate, is less than assured. The fragility of the current downward trend in incidents rests with the endemic root causes that drive acts of piracy and provide the opportunity for such conditions to exist. It would be disingenuous at best, and dangerous at worst to interpret the decline in piracy volumes in 2021 as indicative of any fundamental or lasting change brought about by any one state or initiative. Claims of radically reduced risks within such a short timeframe and calls for the ending of war risk premiums are premature. Whilst regional counter piracy efforts in 2021 are to be commended, they require long term investment, both politically and financially, with on shore investment arguably of greater importance than offshore assets.

Follow us on twitter