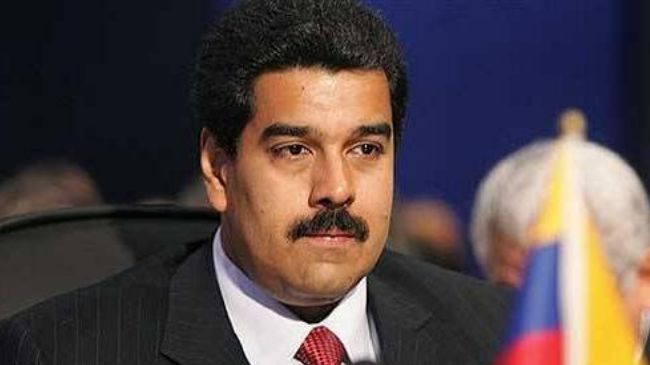

London/Mexico City — The United States is considering an October deadline for ending exemptions to Venezuelan sanctions that allow some companies and refiners to still receive the South American producer’s oil, two sources said, as Washington seeks to raise the heat on President Nicolas Maduro.

U.S. President Donald Trump has ramped up sanctions on Venezuela’s state-run PDVSA, its key foreign partners and customers since it first imposed measures against the company in early 2019, seeking to oust the left-leaning Maduro after a 2018 re-election considered a sham by most Western nations.

Officials in Washington say the failure of sanctions to loosen Maduro’s grip on power has frustrated Trump. With November’s presidential election approaching, the U.S. government is preparing to toughen its stance on Venezuela, especially the sanctions on its oil and gold industries, the sources said.

The sanctions have already deprived PDVSA of most of its long-term oil customers, reducing oil exports to below 400,000 barrels per day (bpd), their lowest level in almost 80 years.

A handful of European and Asian customers have continued taking Venezuelan oil under specific authorizations granted since last year by the U.S. Treasury for transactions that do not involve cash payments to Maduro’s administration.

The list includes Italy’s Eni, Spain’s Repsol, India’s Reliance Industries and Thailand Tipco Asphalt. About a dozen mostly unknown firms also have emerged as customers this year, according to PDVSA’s exports documents.

The U.S. administration is moving to set an October deadline for winding down all trade of Venezuelan oil, including swaps and payments of pending debt with crude, the sources said.

Top envoy says U.S. preparing tighter oil sanctions on Venezuela

“Whatever oil business is left has to be completed (by the deadline),” one of the sources said.

A further tightening of the sanctions on Venezuela’s main export industry would be likely to exacerbate not only chronic shortages of fuel in the South American country but also lack of everything from basic foodstuffs to medicines.

PDVSA, Reliance, Tipco and the U.S. Treasury did not immediately reply to requests for comment.

A U.S. State Department spokesman said they “continue to engage with companies in the energy sector on the possible risks they face by conducting business with PDVSA.”Repsol, which at the end of 2019 registered 239 million euros in unpaid debt in Venezuela, said its operations were fully compliant with international laws.

Eni said it was operating in full compliance with the U.S. sanctions framework and would continue to do so “in continuous dialogue with all U.S. relevant authorities.”

Traders and sources from those companies familiar with export operations from Venezuela said they have not yet been notified of the changes. Almost all PDVSA’s remaining long-term customers have since 2019 requested authorization from the U.S. Treasury to take Venezuelan oil under non-cash contracts agreed with PDVSA as a way to receive payment for pending debts or outstanding dividends, or to exchange Venezuelan crude for fuel. In February, the Treasury’s Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) sanctioned what was then PDVSA’s main trade partner, Rosneft Trading. In March, OFAC followed with sanctions on another unit of Russia’s Rosneft , TNK Trading, and in June it sanctioned two Mexico-based firms that exchanged Venezuelan oil for trucks.

Most buyers of Venezuelan crude have since ceased business with PDVSA to avoid falling foul of sanctions while new -mostly unknown – clients have emerged in recent months, taking cargoes under complicated transactions often involving trans-shipments at sea and multiple re-sales. Venezuela has also recently deepened business with Iran, infuriating Washington, which this month seized 1.1 million barrels of Iranian fuel bound for Venezuela after getting a warrant from a U.S. court.

The United States in April gave U.S. Chevron Corp. and a handful of U.S.-based oil service firms until Dec. 1 to wind down all operations in Venezuela. Chevron had stopped trading Venezuelan crude in March, and in July it wrote down its entire investment in the country.

Chevron did not immediately reply to a comment request.

Even though the U.S. government cites Venezuela’s plummeting oil exports as a success of its sanction policy, some officials privately acknowledge that application has been inconsistent.

(Reporting by Jonathan Saul in London, Marianna Parraga in Mexico City and Humeyra Pamuk in Washington. Additional reporting by Nidhi Verma in New Delhi, Clara-Laeila Laudette in Madrid, Stephen Jawkes in Milan, Devika Krishna Kumar in New York, Jennifer Hiller in Houston, Daphnne Psaledakis in Washington and Chayut Setboonsarng in Bangkok; Editing by Daniel Flynn and Marguerita Choy)