14 October 2017, Cape Town — Sub-Saharan Africa’s economies are experiencing a modest recovery, with gross domestic product (GDP) growth in the region expected to rise to 2.4 percent in 2017 from 1.3 percent last year, according to the World Bank.

14 October 2017, Cape Town — Sub-Saharan Africa’s economies are experiencing a modest recovery, with gross domestic product (GDP) growth in the region expected to rise to 2.4 percent in 2017 from 1.3 percent last year, according to the World Bank.

“This moderate pace remains below population growth,” says the bank, “making it difficult for countries to make a significant dent in poverty unless greater efforts are undertaken to increase the efficiency of investment and to pursue new drivers of sustainable growth.”

Africa’s Pulse, a regular bank report which analyses African economies, “reveal[s] a challenging economic outlook for the region,” adds the bank.

It quotes its chief economist for Africa, Albert Zeufack, as saying that “recovery is weak in several key dimensions, notably, low investment growth and falling productivity growth. This calls for more sweeping structural reforms that can help ensure that economic growth is anchored on a strong footing.”

The bank continues: “The report underscores a decrease in the efficiency of investment, especially in countries with less resilient economies. This is particularly true for skills development in Africa, where countries must reconcile the fact that despite investing heavily in building skills (public expenditure on education has increased sevenfold over the past 30 years), the region continues to have the least skilled workforce in the world.

Verbatim excerpts from the executive summary of the October issue of Africa’s Pulse follow:

Following a sharp slowdown over the past two years, a recovery is underway in Sub-Saharan Africa.

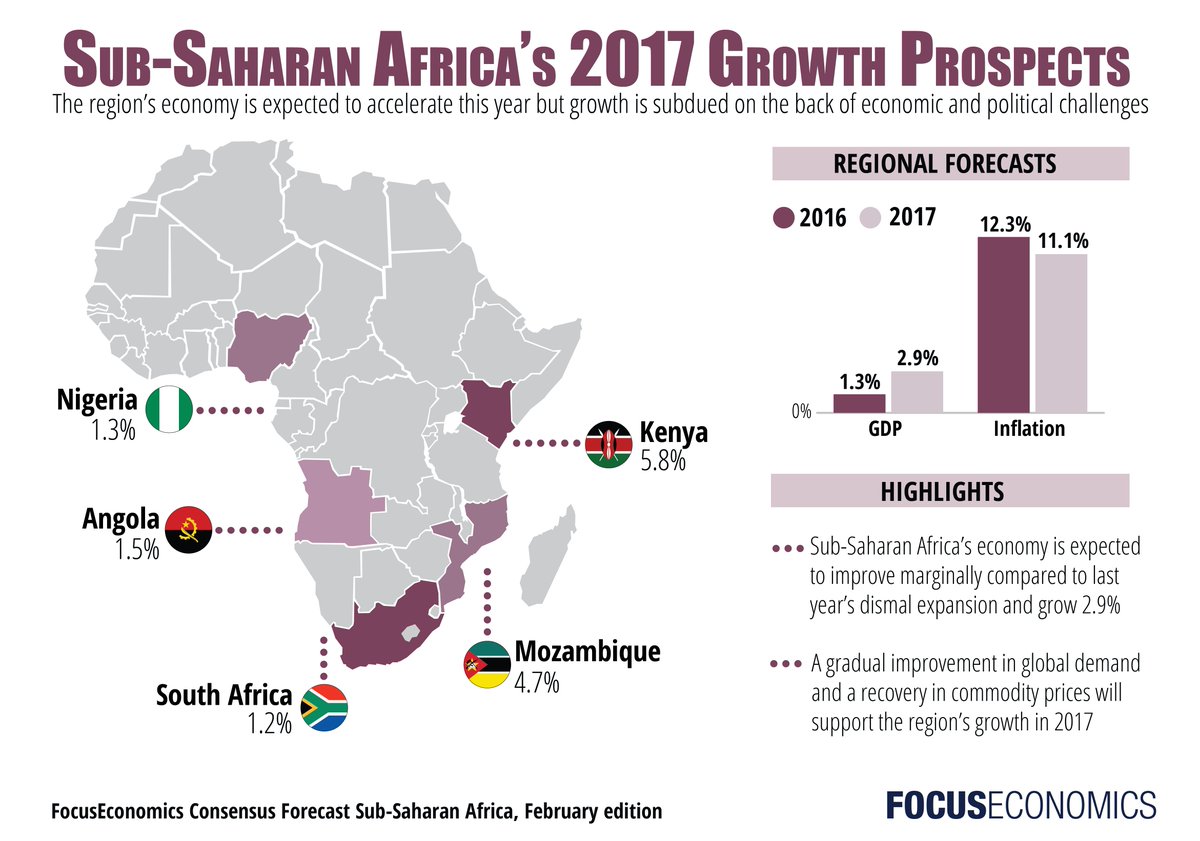

Gross domestic product (GDP) growth in the region is expected to strengthen to 2.4 percent in 2017 from 1.3 percent in 2016, slightly below the pace previously projected. The rebound is being led by the region’s largest economies. In the second quarter of 2017, Nigeria exited a five-quarter recession and South Africa emerged from two successive quarters of negative growth. Economic activity has also picked up in Angola. Elsewhere, an increase in mining output along with a pickup in the agriculture sector is boosting economic activity in metals exporters. GDP growth is stable in non-resource intensive countries, supported by domestic demand. But the recovery is weak in several important dimensions. Regional per capita output growth is forecast to be negative for the second consecutive year, while investment growth remains low, and productivity growth is falling.

External conditions are more favorable, with a stronger trend in global growth, robust growth in global goods trade, rising energy and metals prices, and supportive global financing conditions. Higher commodity prices are helping to narrow current account deficits in the region, especially of oil exporters. International bond and equity inflows in the region are rising, helping to finance the current account deficits and cushion foreign reserves. Sovereign bond issuance has rebounded in 2017, with Nigeria, Senegal, and Côte d’Ivoire selling bonds on international capital markets, indicating improving global sentiment toward emerging and frontier markets.

Headline inflation slowed across the region amid stable exchange rates and lower food price inflation due to higher food production. Reduced inflationary pressures have prompted some central banks to ease monetary policy. Lower inflation and a more accommodative monetary policy is providing an impetus to domestic demand. Fiscal deficits are projected to narrow slightly in the region in 2017, but will continue to be high, as fiscal adjustment measures remain partial at best. Across the region, additional efforts are needed to address revenue shortfalls and contain spending. Government debt remains elevated, reflecting the limited progress made in reducing the fiscal deficit.

Fiscal space has narrowed significantly for most countries in the region in recent years amid rising debt burdens. The (median) increase in general government debt to GDP in 2015-16 compared with 2010-13 was about 15 percentage points. Over the same period, fiscal conditions tightened for 36 (of 44) countries in the region. In these countries, the (median) number of tax years needed to repay the debt fully has increased by 1.1 years; in the Central African Republic, The Gambia, Mozambique, and the Republic of Congo, the increase in this indicator exceeded 2.5 years.

Analysis of fiscal sustainability gaps shows that the pattern of debt sustainability in Sub-Saharan Africa is comparable to that of other commodity-exporting regions.

Fiscal balances in the region fluctuate with the commodity price cycle. Prior to the global financial crisis, the region recorded primary surpluses, thanks to rising commodity prices. Although debt levels remain below those in the late 1990s–when several international debt relief initiatives were implemented–they have been rising more rapidly than in other regions since 2009. The primary sustainability gap, on average, has been negative in the post-crisis period, reflecting the current debt sustainability challenges facing the region.

Looking ahead, Sub-Saharan Africa is projected to see a moderate pickup in activity, with growth rising to 3.2 percent in 2018 and 3.5 percent in 2019. These forecasts are unchanged from April, and assume that commodity prices will firm and domestic demand will gradually gain ground, helped by slowing inflation and easing monetary policy. The uptick in the region’s growth forecast reflects gradually improving conditions in the large economies as they implement measures to address economic imbalances. The ongoing recovery in metals exporters is likely to continue with steadily rising metals prices expected to spur further investment in the mining sector. By contrast, growth prospects will remain weak in Central African Economic and Monetary Community countries, as most of them continue to struggle to adjust to low oil prices amid depressed revenues and elevated debt levels.

The economic expansion in West African Economic and Monetary Union (WAEMU) countries is expected to proceed at a solid pace on the back of robust public investment, led by Côte d’Ivoire and Senegal. Elsewhere, growth is projected to recover in Kenya, as inflation eases, and firm in Tanzania on a rebound in investment growth. Ethiopia is likely to remain the fastest-growing economy in the region, although public investment is expected to slow down.

The outlook for the region remains challenging, however, with economic growth remaining well below the pre-crisis average, and also below the average growth recorded in 2010-14. The moderate pace of growth will translate into only slow gains in per capita income and will be far from sufficient to promote broad-based prosperity and accelerate poverty reduction.

Moreover, although risks to the outlook appear to be broadly balanced in the near term, they remain skewed to the downside in the medium term. On the upside, stronger-than-expected activity in some large economies could strengthen further the anticipated pickup in exports, mining and infrastructure investment, and growth in the region. On the downside, the main risks include, externally, lower commodity prices and a faster-than-expected normalization of monetary policy in the United States, and, domestically, delays in implementing appropriate policies to improve macroeconomic stability, heightened policy and political uncertainty, rising security tensions, and inadequate rainfall.

The challenge for the region remains to achieve high and inclusive growth. In the near term, measures are needed to strengthen the ongoing recovery. Fiscal space remains tight in most countries, and should be enlarged through appropriate fiscal policies that support growth. In the medium term, structural measures will be needed to boost productivity and investment and promote economic diversification. Analysis of the region’s growth dynamics shows that in economically less resilient countries, rising capital accumulation has been accompanied by falling efficiency of investment spending, but not in resilient ones. This suggests that the inefficiency of investment–which reflects insufficient skills and other capabilities for the adoption of new technologies, distortive policies, and resource misallocation, among other things–will need to be reduced if countries are to capture fully the benefits of higher investment.

African countries seek new drivers of sustained, inclusive growth, attention to skills building is growing. The region’s growing working-age population represents a major opportunity to reduce poverty and increase shared prosperity. But the region’s workforce is the least skilled in the world, constraining economic prospects. Building the skills–cognitive, socio-emotional, and technical–of today’s workers and future generations will be vital for realizing the development potential of the region.

Countries in Sub-Saharan Africa have invested heavily in skills building, and public expenditure on education absorbs about 15 percent of total public spending and nearly 5 percent of GDP, the largest spending ratios among developing regions. Although more children are in school today than ever before, almost one in every three children fails to complete primary school. In most countries, far less than 50 percent of all children complete lower secondary education (the equivalent of middle school in some countries), and under 10 percent make it to higher education.

In most countries, skills-building efforts must strive to make spending smarter to ensure greater efficiency and better outcomes. But smart investing in skills is more difficult than it looks. Sub- Saharan African countries face two hard choices in balancing their skills portfolios: striking the right balance between overall productivity growth and inclusion, on the one hand, and investing in the skills of today’s workforce and tomorrow’s workforce, on the other hand.

Investing in the foundational skills of children, youth, and adults is the most effective strategy to enhance productivity growth, inclusion, and adaptability simultaneously. Thus, all countries should prioritize building universal foundational skills for the workers of today and tomorrow. This is more pressing in countries with low basic educational attainment and poor learning outcomes among children and youth.

In skills training, countries must be selective and ruthlessly demand-driven. For productivity growth, support should target demand-driven technical and vocational education and training, higher education, entrepreneurship, and business training programs tied to catalytic sectors. Such support should incentivize more on-the-job training, especially in smaller firms. Special attention should be paid to science, technology, engineering, and mathematics fields, focusing on the transfer and adoption of technology in economies with an enabling policy environment for these skills investments to pay off.

Economic inclusion requires investing in labor market training programs focused on disadvantaged youth and improving the skills of workers in low-productivity activities.